About 65% of the population of India falls in the working age group . This population is the bedrock of India’s famed demographic dividend. However, a large proportion of this population remains unemployed or underemployed even after undergoing technical education . One possible reason for this is the gap between industrial demand and the skill set that the working age population possesses. It is also important to note here that formal technical education takes time to create a skilled workforce but during this time industrial demand keeps evolving. It was against this backdrop that the Skill India Mission was launched in 2015 to create a pool of 40 crore skilled manpower by 2022.

Though several skilling schemes were already being implemented in the country before the Skill India Mission was launched, the mission gave them direction. Most skilling schemes are designed in collaboration with industry associations and implementation entails public-private partnership.

This blog uses Haryana as a case study to explain how skilling schemes are structured and how they can be redesigned to be more outcome-focused.

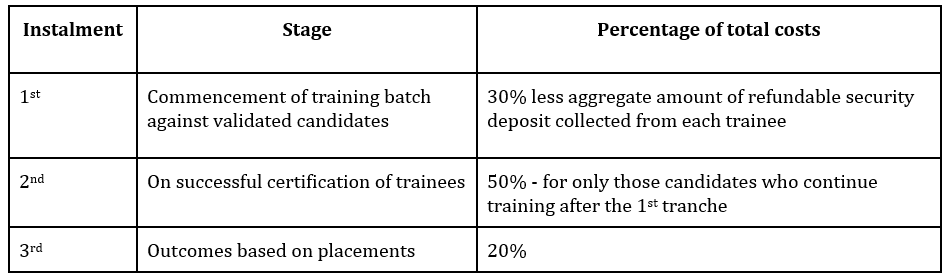

There are currently 15 skilling schemes running in the state which are sponsored by Government of India and managed by Government of Haryana. These schemes either fall under the purview of departments (such as Labour, Animal Husbandry, Agriculture) or under missions (such as Haryana State Rural Livelihoods Mission and Haryana Skill Development Mission). Usually, a skill training course is run at a privately-owned training centre (TC) by a private training partner (TP). One training partner may run several skilling courses at different TCs. TCs are accredited either by the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) or state departments or skilling missions. The targets for training are allotted to the TPs by the department/ mission managing the scheme, candidates are enrolled at the TC and then training begins. During training, TCs are required to maintain the attendance of all candidates. Training is deemed complete when the candidate receives certification after an assessment conducted by partners empaneled by the Sector Skill Councils (SSC). The SSCs were created after the launch of the Skill India Mission to define the job roles, course content and qualification requirements for the trainings imparted to the candidates. It is pertinent to note that candidates do not pay anything for the training. TPs get financial aid for a candidate they have trained based on a fund flow mechanism defined in the common norms for skilling schemes. The disbursal takes place at three stages as given in the below table.

As can be seen, a TP receives 80% of the funds irrespective of whether the candidate gets placed. An analysis of the skilling schemes run by HSDM done by Samagra’s Saksham Haryana - Skills & Employment team, completed in the year 2018-19, showed that the placement percentages for the year were in the range of 12 - 16%. When TPs are given targets that are not aligned with the demand in the industry how would the candidates get absorbed in the workforce? This requirement varies from region to region based on the type of dominant industries. A candidate who stays in Yamunanagar might not get placed there after completing a course in Artificial Intelligence but the same candidate would have a higher chance of getting a job if she had been staying in Gurugram. As such the entire ecosystem is focused on training with little thought on placement post-training. TPs are incentivised to ignore the last installment based on placements which would anyway be 20% of the total cost.

To mitigate these challenges, skilling schemes need to be comprehensively redesigned.

- At the target allocation stage, a free hand needs to be given to the TP to choose the relevant sector / course based on total training targets announced by the relevant central or state authority. Being closer to the ground, a TP would have a better sense of what job roles are in demand in the region. A TP should be given at least a three-year target distributed across sectors. A long-term relationship will also allow the TP to plan better.

- TCs should make information on the number of candidates enrolled, certified and placed public. Prospective trainees should have visibility about the outcomes associated with each course offered by each TC.

- Financial support from the Centre or state governments should be linked only to placements. The last two installments should be subsumed into one - certification and placement. This would result in TCs establishing partnerships with industries and enrolling candidates based on the number that can be successfully placed.