One of the biggest joys while solving a data science problem is the realization that the data needed to solve the said problem is actually available. This joy is even more profound when solving a problem related to government data. The flip side, however, is that data collection in the government ecosystem is often like a game of Chinese Whispers.

We confronted this challenge in Odisha, when we tried to collate all farmer details in a single database after sourcing it from multiple datasets. Information such as demographic details of farmers, bank account, cropping patterns etc., often present across multiple platforms, were in conflict with each other by sometimes giving completely different values. For example, for the same farmer, the type of crop grown was millet in one data source, paddy in another, with no definitive way to verify the true value. It became very critical for us to estimate the confidence score i.e. the probability that the provided data point for each farmer in each data source was the truth.

At first glance, this seems like a simple fact-checking exercise–there are now entire organizations working on fact checking. However, what compounded the problem in this case was the scale. We had information for nearly 74 lakh farmers from across 14 databases and for more than 90 data fields, with many of these fields having multiple conflicting values across different data sources.

But, why did we need to collate and match all the farmers’ data in the first place?

The Department of Agriculture & Farmers’ Empowerment (DA&FE), Government of Odisha implements multiple technology-driven schemes such as KALIA, Seed Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT), AMA Krushi. However, the provision of these schemes depended on data systems that existed in silos and seldom talked to each other. As a result, farmers would have to register separately for all of them and undergo eligibility determination each time they applied. On the other side, the government would need to verify these applications through repeated rounds of field and document verification. As a first step to mitigate these issues, the Government of Odisha conceptualized Krushak Odisha—a state-wide comprehensive farmer database. The database will contain the latest demographic, financial, land record, and asset-related information of all the state’s farmers.

Accurate data on these parameters will empower DA&FE to streamline agriculture extension services to farmers. At the gram panchayat and block level, officers can plan and identify farmers periodically for interactions, training and scheme dissemination using farmers' data from the database. Advisories like the variety of seeds to be used, strategies for prevention from pest attacks can be targeted and customized at a more granular level keeping in mind the location of land, type of land, access to irrigation for each farmer.

Consented information on farmers will be available to other government departments and ecosystem players like Food and Civil Supplies for procurement operations, Odisha Livelihood Mission for Farmer Producer Groups formation and training, and financial institutions for better credit linkages.

The government will now be able to create a platform on top of the Krushak Odisha database to connect farmers with aggregators, traders and entrepreneurs within and outside the state. Access to accurate location and produce information about farmers will help industries make informed decisions about setting up operations like warehouses, aggregation and quality operations. However, third-parties wanting access to relevant data through APIs will require prior approval from DA&FE and consent from the farmers; they will also sign a data-sharing agreement with the department. The agreement will prevent third-parties from misusing the data.

How could we solve this, does the world of data science have some established solutions?

After exploring multiple options, we realized we were looking for solutions in the realm of truth-discovery. There is no ‘absolute truth’ or completely verified datasource to help us estimate any source’s accuracy. Hence, we can’t use any supervised learning techniques (which can ‘learn’ relationships between true and estimated values) Truth discovery here becomes pretty similar to imposter games like Among Us. The algorithm needs to guess the true values from a mixture of true values and imposter false values based on some assumptions on how true values would look compared to false ones.

These methods often calculate a confidence for each fact provided by the data sources and pick the fact with the highest confidence as the ‘true value’. Truth discovery methods can range widely from extremely simple ones like picking the most common value amongst the sources as the true value to more complicated ones which involve the use of iterative algorithms, Bayesian networks or Deep Learning to understand the relationships between data sources and possible truth. However, all of them rely on some basic heuristics on how the true values differ from false when one is provided with a set of true/false facts on the same data point.

The heuristics of ‘Truth Finder’ algorithm (the one we used) are listed below:

Heuristic 1. There is only one true fact for a data point.

Heuristic 2. This true fact appears to be the same or similar on different sources.

Heuristic 3. The false facts on different sources are less likely to be same or similar

Heuristic 4. A source that provides mostly true facts for many objects will likely provide true facts for other objects.

So, how do the algorithms use these heuristics to come up with the confidence score for each data point?

The Truth Finder algorithm is one of the foundational approaches to solving this problem. It uses an iterative approach similar to Google’s famous PageRank (which measures the importance of a webpage on the basis of number of links to the page) but considering the reliability of websites instead of number/quality.

The steps for the Truth Finder algorithm are given below:

- Assume an average confidence of each source - usually set to 0.5 for all sources

- Calculate the confidence scores for each data point across all data sources: This is the crux of the entire algorithm. The confidence score calculation is a logistic log transformation of the probability of a fact being correct given average correctness of each source and the matching amongst the data points

- Recalculate the average confidence for all sources by averaging across all data points for the source

- Continue iterating the above 2 steps till the average source confidence values don’t change from one iteration to the next

- Get final confidence values for each data point from the final average confidence of each source

How do we know if this actually worked?

Ideally, we would like to just build the confidence scores and walk away, but the entire agri-tech ecosystem is unanimously (and perhaps rightfully so) suspicious of the effectiveness of research-based algorithms on real world data.

So, how did we prove that these scores actually make sense?

There is no mathematical sleight of hand here, instead we decided to get our hands dirty and went for ‘ground-truthing’. This entailed actually calling up a sample of farmers (9,000) in Odisha, reciting the data shown by our database, asking if it was correct and getting another estimate of the ‘correctness’ of the database directly from the source itself.

We calculated the accuracy of the data points from the ‘ground-truthing’ exercise and for all the data points having the same confidence scores, compared the ‘confidence values’ from our algorithm and the ground-truthing. We then checked the weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) between the two confidence scores for 20 sample fields and arrived at an overall error of 13% and a significant correlation even if the scores had some error.

Not a bad start for an unsupervised algorithm.

This is the story of how we managed to give a ‘confidence’ score for the reliability of our data points for each farmer. We now plan to look at all the data points with low reliability, create a feedback mechanism to check against sources and iteratively improve the reliability of the whole database. This process can be replicated for any scenario where there are multiple conflicting data sources for the same data field.

What happens if the confidence score of a data point goes below the defined threshold?

Given the number of critical schemes and services that the government has to deliver to farmers, it is in the interest of both the government and farmers that a state-wide comprehensive farmer database remains updated with accurate data points. However, deployment of a confidence algorithm will only help us in monitoring the data quality and not actually improving it over time. What about the data points whose confidence levels are below the defined thresholds? More so, what about the farmer profiles whose overall confidence level is below these thresholds?

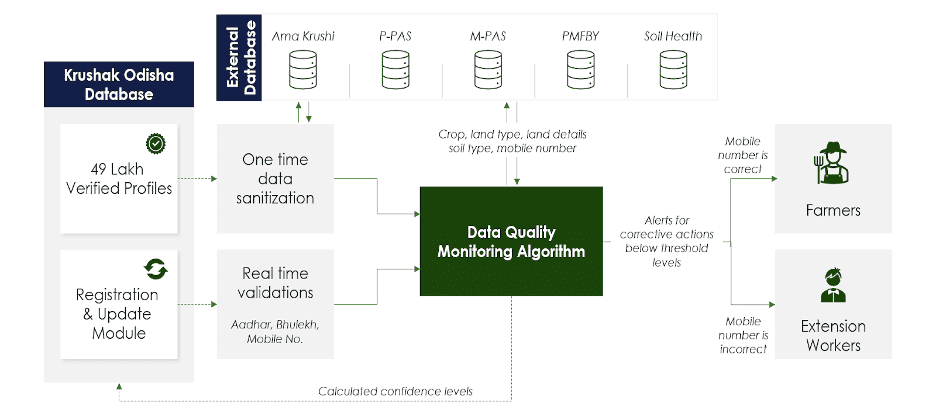

Continuous data quality monitoring is the first step towards ensuring accuracy of data in a database. Confidence thresholds will be defined for each data point to ensure useability of that data by the government and ecosystem players. The confidence algorithm will calculate the confidence levels of each data point at a monthly frequency, and flag all farmer profiles having data points with confidence levels less than the defined thresholds.

Once we are able to identify the farmer profiles with the exact data points that are potentially inaccurate, the government will notify these farmers via SMS to correct their data and update their profiles on the Krushak Odisha portal at their nearest Mo Seba Kendra (a Common Service Center equivalent in Odisha). In case the confidence score of the mobile number of a particular farmer is itself low, the government will notify the extension worker designated at the farmers’ Gram Panchayat to nudge the farmer to update their data.

Key Learnings

- We should always compare and verify amongst multiple sources for a data point - we need not choose between sources, we can combine them effectively to get the best data quality possible.

- The Truth Finder algorithm is an easily deployable, quick and effective system for getting confidence scores for data features with fewer (<40) conflicting data sources.

- We should make sure our separate data sources are ‘independent’. We cannot have 2 sources that are sourcing the data from the same parent source and thus have matching facts.

- The government machinery can operate at an unthinkable scale for any task. We were able to manually verify facts for thousands of farmers just to test an algorithm.

On the whole, the exercise was a great example of how much data science has to offer in solving complex governance problems. For any citizen service delivery, data accuracy is of paramount importance in ensuring that schemes and services are customized for the right target group and delivered in a timely manner. Yet, very often the reliability of data in government systems is low. The confidence algorithm is a small step in addressing this gap, by providing an effective way of measuring the reliability of data and an opportunity to iteratively improve it. The successful deployment of this in Odisha is a significant breakthrough for the government and will go a long way in helping create a consolidated accurate database to help cater to all farmer needs in the state.

Annexure

1. Why are we following the Truth Finder Algorithm to calculate the confidence level of our data points? Is there any precedence establishing that this is the best/ideal way to go about it?

- The Truth Finder algorithm is a well-known research paper cited extensively in the data science world including by Google for its Knowledge-based-Trust Algorithm which is Google’s patented method of carrying out truth-discovery to improve its search results. It's based on the same iterative principles as Page-Rank but considering the reliability of websites instead of number/quality.

- The model is completely data driven and does not require estimating any accuracy parameters.

- The model is relatively simple to implement, runs quickly and does not require expensive infrastructure.

- The model works well with a low number of data sources (most truth discovery models are built for websites and often scrape from thousands of websites to check).

- The model has been implemented previously as Open Source code in Java/R.

2. Where has this model been implemented previously? Can we get some test results or evidence of success for this model?

The Truth Finder consistently displays good results for truth discovery on real world data sets. In this work, it was tested on the following datasets:

- The AbeBooks data set: It’s a comparison of author details for computer science books extracted from AbeBooks websites in 2007 It consisted of 33,235 claims on the author names of 1,263 books by 877 book seller sources. The ‘true value’ was available for 100 randomly sampled books for which the book covers were manually verified by the authors. The Truth Finder algorithm had an accuracy of 94% which was 2nd best amongst algorithms compared with the least computation time.

- Weather data set: The Weather data set consists of 426,360 claims from 18 sources on the Web for 5 properties (temperature, humidity etc) on hourly weather for 49 US cities between January and February 2010. ‘True value’, was deemed to be the AccuWeather website values which were available in 75% of the cases. The Truth Finder algorithm had an accuracy of 86% which was the best amongst all algorithms compared with the least computation time.

- Biography data set: The Biography data set consists of 9 biography details (father name, mother name, age etc) extracted from Wikipedia with 10,862,648 claims over 19,606 people and 9 attributes from 771,132 online sources. The Truth Finder algorithm had an accuracy of 90% which was the 2nd best amongst all algorithms compared with the least computation time.

- Population data set: The Population data set consists of 49,955 claims on city population extracted from Wikipedia edits from 4,264 sources. The ‘true value’ was considered to be the official US census data. The Truth Finder algorithm had an accuracy of 87% which was the 2nd best amongst all the algorithms.